Overview

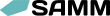

This document explains how SAMM security practices work for Agile to attain the continuous building in of sufficient security during software development. It’s structured in the form of best practices and pitfalls.

Why SAMM Agile guidance

The Software Assurance Maturity Model (SAMM) is an OWASP flagship project on how to set up and grow a secure development process. It is agnostic of the development approach, which is why Agile is not explicitly covered. Nevertheless, there appears to be a strong need in the industry for guidance on how to make secure software development work in an Agile environment. How do you squeeze all the necessary activities into a sprint, e.g. requirement selection, threat modeling, verification? What do you do with stories, with abuse stories and with the Definition Of Done? How do you get security teams and developers to co-operate instead of just setting up quality gates?

There are three main reasons for SAMM Agile guidance:

- It provides specifics on how the activity is (slightly) different for Agile.

- Additionally, it provides more detail on how to implement activities in Agile (for example how you make code reviews incremental), and what pitfalls to watch out for. Many mistakes are made in practice when doing software security, especially in Agile situations.

- It prevents SAMM from being regarded as ‘too much waterfall’.

History

Since April 2018, Rob van der Veer has been working on extending SAMM with this guidance, in collaboration with the SAMM working group, industry peers and clients. These peers notably include Michael Kuipers (Centric) and Eric Nieuwland (ICTU). The Agile guidance was developed by studying many organizations on what works and what doesn’t work, by doing interviews and by looking into the many publications on this topic.

In this document

- General

- Quality at speed

- Does a maturity model conflict with Agile?

- Education & Guidance

- Team autonomy

- Security is a shared responsibility

- Strategy & Metrics

- Metrics

- Threat Assessment

- Incremental threat modeling

- Security Requirements

- Selecting and preparing requirements

- Requirements in stories

- Security Testing

- Agile testing

- Requirements-driven Testing

- Abuse stories

General

The goal: quality at speed

How to attain quality at speed? Agile delivers software more frequently, which means that quality assurance is a more frequent issue. Traditionally, quality assurance has been a carefully designed single phase in software development. The challenge is to make it less bureaucratic, take less time and still get quality software. To make this feasible, mistakes need to be both prevented (build security in) and fought (find mistakes) with maximum efficiency, so to minimize manual work and the burden on developers:

Prevent

- Use solid technologies/frameworks/components that take care of as much security as possible

- The remaining requirements are clear and applied situationally as much as possible, so to reduce the number of requirements that need to be dealt with all the time

- Responsibility and understanding of security principles with all people involved, including the product owner

- Feasible and therefore situational instructions for developers. No stacks of books but clear short lists, selecting requirements based on the specific task at hand

- Good changeability of code (maintainability) to minimize errors

Fight

- By checks that need to be automated as much as possible

- Manual checking will still be required and needs to be performed in a smart incremental and risk-based way, focusing only on changes and their impact.

The SAMM Agile guidance provides insight into how to make this happen.

Does a maturity model conflict with Agile?

A maturity model may appear to conflict with the Agile manifesto, because Agile holds people over process and working software over documentation. However, Agile does not disqualify process or documentation - it wants to minimize it where possible. To make this happen, a maturity model can provide tremendous help and it supports the Agile way of improving the way you work by learning as you go along.

Education & Guidance

Team autonomy

In most Agile environments, team autonomy is important, which means that it can be a challenge to work on process maturity at an organization-wide scale. If team-autonomy is important, then a maturity program should embrace that different teams can have different maturities and different ways of working, including security. At the same time it is advisable to let teams learn from each other, so sharing of practices between teams is a best practice for maturity programs, as well as transparency on maturity which nurtures gamification.

In order to have security on the team’s agenda, it needs to be a standard topic in both refinements and retrospectives. Over time, teams learn which security concerns took much effort/are underestimated. That experience makes planning more precise and predictable. A security specialist (who could be the security champion) can be of tremendous help during these sessions to fill in the details and knowledge gaps.

Security is a shared responsibility

In an Agile environment, security needs to be built in from the start. There is no time every sprint for the approach of building features without worrying too much about security, then do security testing and then fix the weaknesses. First of all, this would require undirected full testing every time and it would require much rework, leading to a situation where the product owner and development team are fighting it out with the security team. Therefore, security needs to be owned by everyone including the product owner. This puts security professionals much more in an advisory and supportive role than in a role of a quality gate that has different stakes than the team. By including security in the discussions and in the planning, there’s no room left to ignore it.

While maturing secure software development, at some point there can be a bottleneck dependency on security expertise, which is why it’s important to strive for team autonomy and promote team members learning from security experts. This way, together with streamlining the process and automation, security becomes scalable.

PITFALL #isolatedsecurity

In some organizations, security is unfortunately organized so that the ‘security department’ verifies the software and then needs to convince the ‘business’ to fix the issues found. This is typically the case when business value is measured in the number of features and security is seen as a cost center, instead of a necessary quality to prevent damage and protect the business value. If product demos are a regular practice, it helps to show what has been done for security, next to the ‘business features’. That way stakeholders and developers experience the importance.

Security Champions

A security champion is a liaison between developers in a team and information security. They act as a point of contact for security-related questions and try to remove any impediments preventing the team to be able to develop software securely. Because of continuous collaboration in Agile, this role is very important.

PITFALL #relyonthechampion

Care should be taken to ensure that security is not delegated as a responsibility to a single developer. The champion can be responsible to help where possible, but that should not relieve the team of security concerns.

PITFALL #silentchampion

Regarding selecting the right champion: the ability and the mandate of the champion to communicate and learn should be more important aspects than technical knowledge.

See Organization and Culture in the SAMM Model.

Strategy & Metrics

Metrics

In Agile, feedback loops are short and verification is frequent. You cannot control what you don’t measure, so in order to put security on the agenda and to improve maturity and quality of results, it is beneficial to measure those aspects. Ideally these measurements are presented in one or a series of dashboards which a central security team together with management can use to drive important decisions.

See Metrics in the SAMM Model.

Threat Assessment

Incremental threat modeling

Even though the Agile manifesto states “working software is more important than comprehensive documentation”, the concept of a threat model should not be dismissed. First of all, a threat model provides a shared mental model of possible attacks in a development team which decreases the probability of security mistakes. Second of all, a threat model can be helpful in selecting the right requirements: system-generic and story-specific (see “Requirements in stories” and “Selecting and preparing requirements”).

The entire threat modeling process doesn’t have to be done all over again every time. It can be done incrementally as the software evolves, by assessing for every new story whether it introduces a new component, process, dataflow or trust boundary. If it does, it can be helpful to extend the existing threat model and identify the new threats and their countermeasures (in the form of functional security stories or requirements for the new story). If the threat model is an important method for the team to build security in, then the system threat model should occasionally be completely reworked, as mistakes tend to build up, incremental change after incremental change.

When applied incrementally, a lightweight version of the four steps can be used, based on the main questions: what are we doing, what can go wrong, what are we doing to defend against threats, and validation of previous steps.

Involving the product owner is recommended to get a fast reality check regarding domain context, economical sensibility of the measures, and to nurture the combined sense of security ownership.

PITFALL #onlythreatmodel

Threat modeling should not be relied on as the only way to build security in. It’s typically hard for developers and for QA people to think like attackers and come up with all the things that could go wrong and all the necessary countermeasures. This is why it’s so important to have security requirements readily available to be selected when specific types of work are done (See “Selecting and preparing requirements”). This hardening approach to security (security hygiene, if you will) nicely complements the risk-based approach of threat modeling as another perspective to see how security needs to be built in. The team can let the amount (effort and frequency) of threat modeling depend on how much they trust the other methods of applying security requirements.

See Threat Modeling in the SAMM Model.

Security Requirements

Selecting and preparing requirements

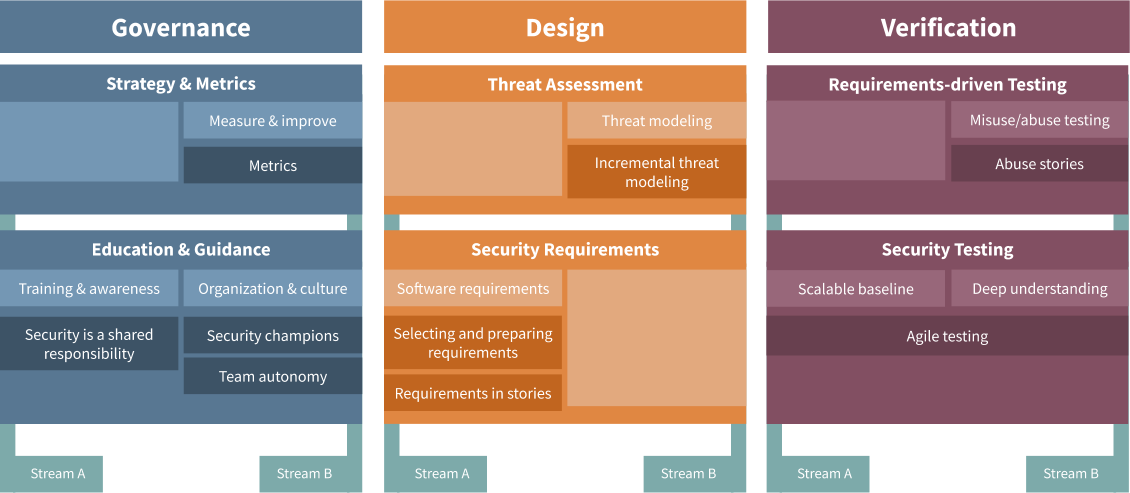

In an Agile process, some requirements need to be selected and tested for every sprint. In order to make this feasible, we need processes to select and prepare relevant requirements per system and per story. The goal is to make the story-process efficient and provide a minimized set of relevant requirements for each situation, including instructions for developers and test plans.

Per system

Before development starts, requirements can be selected from the set of standard requirements, which are typically established on an organization level - taking into account industry standards and compliance. This selection process is based on the context of the software (domain, role, risks technology choices, run-time environment) and needs revisiting when this context changes. Risk analysis is a typical part of this process. Per non-functional requirement, the following options exist in the selection and preparation:

- Not applicable in the context

- Applicable but risk accepted

- Covered by the technology used (e.g. framework/library providing, for example, input validation)

- Needs system-generic or story-specific instructions X and tests A, B, C (e.g. automated static scan, automated dynamic test, manual test, code review, or a combination). For story-specific requirements, the criteria need to be described when it is applicable - the so-called trigger.

After this selection and preparation, system-generic requirements are referred from the Definition Of Done, whereas story-specific requirements are made available in a pick list, grouped by the triggers, that allow later selection of the right requirements depending on the type of work being done in a story. Picked story-specific requirements become part of a story’s acceptance criteria in the form of instructions for developers and tests to be performed. The prepared and selected requirements can also function as input to a training program.

To summarize: the deliverables of the per system selection and preparation are:

- A pick list of requirements that need to be applied situationally, per story, based on triggers

- A Definition Of Done, with a list of requirements that always need to be applied

- A selection of above requirements that need to be included in developer training

- A list of requirements that were deemed not applicable or acceptable risks (which can be based on balancing security with effort or compromises in usability/performance etc.)

Each requirement has a short name or number, a description of the risk, instructions for developers, automated tests, and instructions for testers/reviewers.

Per story

Picking specific requirements for a story is done during creation of the story and during backlog refinement, if necessary with the help of a security expert. There are different ways to pick the requirements:

- Using triggers from the pick list: in case requirements are prepared with ‘triggers’ these can be used to determine whether requirements fit the story.

- Using expertise: security expertise can help to efficiently select the proper requirements for a story.

- Using abuse stories (how the system can be attacked): they can help to identify weaknesses and thus link to the right requirements.

- If the methods above provide insufficient confidence: use threat modeling.

Triggers are, in other words, descriptions of functionality or architecture that need specific sets of requirements. For example: “user forms” (for requirements on validating user input), “session” (for requirements on tokens, time-out etc), or “storing passwords” (for requirements on hashing).

The requirements are put into the acceptance criteria of the story. This informs developers what should be taken into account to plan and perform the work, and adds to the necessary tests.

Instructions

Requirements contain rules that the software needs to comply with. These rules are not ideal as instructions for the developers. It helps to have separate instructions in which criteria that are expected to be known are left out, and other criteria are phrased from a developer’s point of view. The goal is to have a small and manageable set of instructions for the developers to take into account. As a result, some requirements might even have no instructions at all, while they still have tests. This is the case where the organization relies on the developer knowledge on the specific matter.

See the diagram below for an overview of the software development process and the flow of requirements.

PITFALL #requirementoverload

Having too many requirements can be too much to ask for developers to constantly be aware of, and can be too much effort to test every time. The goal is therefore to cover as many requirements as possible by the technology/architecture used and aim to have as many requirements as possible depend on the type of work in a story.

PITFALL #forgettheframework

Frameworks and libraries can cover part of the security requirements and therefore it should not be forgotten to ensure that these frameworks and libraries are being used. Often, developers can easily work their way around existing facilities, whether on purpose or by neglect. In other words: the proper application of frameworks and libraries should be either technically enforced or part of specific or generic test procedures.

PITFALL #abuseCOS

In case a team works with the “conditions of satisfaction” these should not be used for security requirements because these are typically about functional behavior. Furthermore, story-specific requirements should not be in the Definition Of Done either - because these are user story independent.

PITFALL #onlythreatmodeling

Threat modeling should not be relied on as the only way to build security in. It’s typically hard for developers and testers to think like attackers and come up with all the things that could go wrong and all the necessary countermeasures. This is why it’s so important to have security requirements readily available to be selected when specific types of work are done. This hardening approach to security (security hygiene, if you will) nicely complements the risk-based approach of threat modeling as another perspective to see how security needs to be built in. The team can let the amount (effort and frequency) of threat modeling depend on how much they trust the other methods of applying security requirements.

Requirements in stories

See also: “Selecting and preparing requirements”. Stories need to be equipped with the relevant non-functional requirements, to be put in the acceptance criteria of the story, based on the type of work expected. This informs developers what should be taken into account, it adds to the necessary tests and it provides the information necessary to plan the work. Equipping the stories is done during the creation of the story and during backlog refinement, if necessary with the help of a security expert if developers have difficulty with this. There are different ways to collect requirements:

- Using triggers: in case requirements in a pick list are prepared with ‘triggers’, these can be used to identify if requirements fit the story (for example when storing passwords: apply specific hashing)

- Using expertise: security expertise can help to efficiently select the proper requirements with a story

- Using abuse stories (how the system can be attacked): they can help to identify weaknesses and thus link to the right requirements

- Using threat modeling exercises (see “Incremental threat modeling)

PITFALL #skipsecurityrequirements

The key to Agile security is to apply the right requirements at the right time. If stories don’t mention security requirements, it is much easier to forget them, also because no time was planned for them.

PITFALL #pickduringplanning

Picking requirements should be done during either creation of the story or backlog refinements. Doing this during sprint planning is not recommended because all the time will be needed to plan.

See Software Requirements in the SAMM Model.

Requirements-driven Testing

Abuse Stories

An Abuse story (or evil story) is a description from the perspective of an attacker (as supposed to a user), how a system is abused through a security weakness: “As an attacker…”. It is normally not added on a sprint backlog because it does not describe specific development work that can be planned. The purpose of an abuse story is to help the team think about what could go wrong so they can specify the work/the requirements needed in user stories. The form of the abuse story is helpful because developers are familiar with user stories. Abuse stories are advantageous mostly at the beginning of development. Abuse stories can be helpful as an explanation of certain security tests, explaining for example to a pentester against what threats a specific requirement needs to be tested.

PITFALL #abusestorygalore

Abuse stories should not be the only method to find security requirements (see “Requirements in stories”). Requirements can also be added by applying triggers, expertise, and by using triggers, allowing more direct and efficient selection instead of first having to think about what could go wrong.

See Misuse/Abuse Testing in the SAMM Model.

Security Testing

Agile testing

In Agile, testing happens more frequently and typically covers the same parts of a system over and over again, which is why it is important to automate testing as much as possible and to limit manual testing based on the changes made.

Security test automation can be done by programming tests on unit and integration level, and by deploying test tools. Important test tool categories are dependency check tools (SCA), dynamic application security test tools (DAST), static analysis tools (SAST). The output of SAST and dependency tools typically contain many false positives that need to be manually checked.

Not all testing can be automated. For example, SAST tools are limited to certain categories of issues in code. The necessary time-consuming manual testing can be minimized by basing it on the expected effects of the changes. For code review, this means that review needs to focus on changed and added code only and therefore requires a structured approach and administration. For manual pentesting this means that the testing should focus on the behavior that is likely to be affected by the changes made. Because the behavioral effect of changes is hard to predict, mistakes may be made in limiting the pentest, which is why it is recommended to do a complete penetration test when the risk of such a mistake is deemed high.

The need for change-based selection of tests shows that especially for Agile it is important to have a modular system, in which modules can be tested separately and there is limited propagation of changes. In an Agile environment there typically is not a budget for in-depth expert manual review and testing after every sprint. This means that in release planning it should be taken into account when such manual work is expected to be necessary, so it can be prepared and planned.

A best practice in Agile is to have QA competence in the development team - this needs to include security testing competence.

PITFALL #skipmanualtest

Automation alone will typically not do the trick. Both expert code review and manual pentest should be part of any software quality assurance.

PITFALL #latepentest

The classic penetration test pitfall is performing it late, just before a public release: when rework is the most expensive and time is the shortest.

See Security Testing in the SAMM Model.

Author

Rob van der Veer (Software Improvement Group) with the help of many peers and clients.